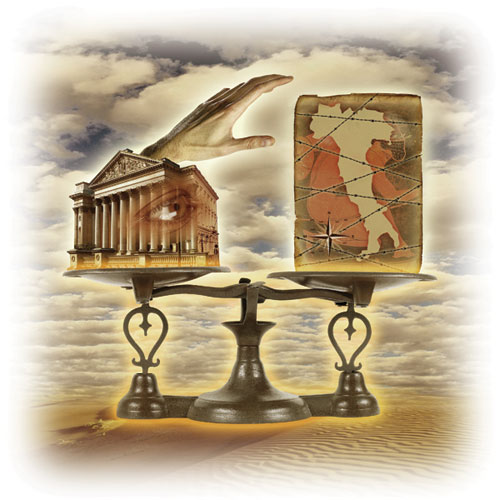

Insider: Guardians of Antiquity?

By Roger Atwood

In 2005 and 2006, I gave public tours in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston of antiquities that were known or widely suspected to have been looted. I took groups of 15 or 20 through gallery after gallery, showing how lack of provenance indicated the likely illicit origin of Maya vessels, Iraqi cuneiform tablets, Greek funerary gold, and dozens of other artifacts. I discussed the history of looting associated with the pieces, which is often more than is known about the objects themselves.

The idea was not to increase the pieces’ notoriety–many were famous enough. It was to show how museums were doing a disservice to the historical record by acquiring huge numbers of antiquities that could have reached them only through looting and illegal export. One piece on my Boston tour was a red Apulian amphora that had no information on its exact origin and had been acquired in the early 1990s–a time of rampant grave-robbing in southern Italy.

“This piece has loot written all over it,” I remarked at the time. Within a year it was gone, returned to Italy by the MFA, along with a dozen or so other pieces, in the face of overwhelming evidence they had been illegally dug up and smuggled to America.

One goal of these tours (which were organized by the group Saving Antiquities for Everyone) was to puncture the smug arrogance with which museums had passed themselves off as custodians of the past. Often enough, they have acted as agents of its destruction, even after 1970, when the world was officially put on notice that the antiquities trade was really a loot trade that cheats us of the chance to know more about the ancient past.

That year, delegates gathered in Paris to draft the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. It was the first major piece of international law committing governments to combat together the trade in objects derived from plundering archaeological sites. In the early 1970s, reports of heavy looting from Sicily to Guatemala circulated widely, and the convention was drafted amid a feeling of genuine urgency. It acquired its legal teeth in a given country only when that country ratified it and passed implementing legislation. (The United States did so in 1983.) Yet the convention’s real power was its moral force. From then on, no one could possibly plead ignorance about what the antiquities trade was really about: “theft, clandestine excavations, and illicit exports,” said the convention.

Until now. James Cuno, president and director of the Art Institute of Chicago, posits in his new book Who Owns Antiquity? (Princeton University Press, $24.95) that the UNESCO treaty and laws enacted around the world aimed at applying its principles have done nothing to stop looting and have succeeded only in inhibiting the global movement of art. UNESCO, he argues, has impoverished our understanding of one another and contributed to a stale, narrowly nationalistic view of culture.

More specifically, these laws have prevented museums like his from acquiring antiquities as they have in the past. He calls them “nationalist retentionist cultural property laws,” and views them as one outcome of what he sees as the chauvinistic nationalism that has infected governments and led to the suppression of minorities and even ethnic cleansing. Whatever good intentions UNESCO had back in 1970, they’ve gone horribly wrong, implies Cuno. And part of this owes to the fact that nationalist retentionist values, he says, are not democratic. According to Cuno, they are profoundly elitist. Government elites decide what the national culture is and pass laws barring the export of art that reflects that culture; everything else is junk. Then they compound the damage by demanding that museums in Western countries return prized artifacts to their countries of origin, which deprives visitors to London, New York, and Chicago of enjoying the wonderful works of art that they have grown accustomed to seeing.

Cuno is an influential figure in American art, and his book offers perhaps as complete a guide as we are likely to get on the prevailing thinking in museum boardrooms. He opens with descriptions of prize pieces from the Art Institute that demonstrate both the breadth of its collection as well as the unique power of the “encyclopedic museum” to draw parallels between the art of different civilizations.

One example is a 16th-century West African bronze plaque that the museum acquired in 1933, one of several hundred such objects taken by a British military expedition from the royal city of Benin a few decades earlier. About 30 are in the British Museum. Nigeria now wants them back. It might seem that Nigeria’s claim is at least worthy of consideration–these artistic masterpieces were seized by force and now sit in distant museums. But Cuno’s aim is to show that if his museum could acquire a piece like this in 1933, it should be able to acquire it now. A lot has changed since 1933, but antiquities collecting, in Cuno’s view, need not be one of them. What’s standing in the way are governments that illegitimately “claim ownership of the world’s ancient heritage” and practice what he calls identity control–the use of cultural property ownership laws to create and enforce a national identity based on what Cuno feels are spurious connections to the ancient past. “And archaeology and national museums are used as a means of enforcing that control,” he writes.

As for UNESCO itself, Cuno is clear. The United States should renounce the convention. He draws a parallel with the Bush administration’s decision to ignore international prohibitions on torture: “We know from the actions of the current Bush administration that long-standing international agreements, like the Geneva Convention, can be ignored or partially adhered to in the presumed national interest of the U.S.”

The analogy with the Geneva Convention is more apt than he realizes. The information given by a prisoner while he is being tortured is unreliable. So is the information given by a looted antiquity; it has been wrenched from its archaeological context and stripped of its basic history. In certain instances, even its authenticity cannot be definitively ascertained. In any case, Cuno does not explain how ignoring the 1970 convention would advance his goal of ending restrictions on antiquities imports. The convention’s basic enforcement mechanism was codified in U.S. law under the Cultural Property Implementation Act of 1983 and signed by President Ronald Reagan. It’s the law of the land, and would remain so even if UNESCO itself disappeared. Under this legislation, the United States has signed bilateral agreements with 12 “source countries” banning the import of unlicensed antiquities from them.

Cuno quarrels with these bilateral deals, particularly one signed with Italy in 2001 in one of the last acts of the Clinton administration. The agreement prohibits the import to the Unites States of nearly all unlicensed antiquities originating in Italy dating before the fourth century a.d. Combined with Italy’s own laws prohibiting antiquities exports, the agreement has almost stopped the legal flow of Italian antiquities originating in Italy to the United States. Even taken together, Cuno says, these laws have failed in their stated aim of ending the plunder of historical sites.Stopping looting is hopeless.

“Archaeological sites will continue to be looted,” he writes, “so long as there are people anywhere in the world willing to pay money for looted antiquities, and so long as there are people living in poverty and the chaos of war and sectarian conflict who are willing to break the law to uncover and sell them.”

But Italy is not exactly known for “poverty and the chaos of war.” It’s one of the richest countries in the world, and yet police there struggle to keep ahead of looters. Turkey and China, the two other countries Cuno discusses at length, do not fit his description very well either. What keeps looting going isn’t poverty or war, but market demand for antiquities. Although Cuno seems to understand this fact, he will not concede that it implicates buyers in the problem. But it does implicate them, and therein lies the fundamental dishonesty of his argument. He goes through the motions of deploring looting but then advocates the activities that cause it, suggesting it cannot be stopped–so why even try? Before long it’s clear that in Cuno’s mind, destruction of the archaeological record is a small price to pay for the enlargement of encyclopedic museums.

People all over the world battle daily against the illicit antiquities trade, and some are seeing modest success–the new archaeology police force in Afghanistan, high-tech Carabinieri units with aerial surveillance in Italy, National Park Service rangers in Colorado, and rural citizens’ patrols in Mali and Peru. Cultural property protection is an area of growing resources and remarkable experimentation. Officials in Italy and Peru affirm that bilateral agreements with the United States have helped cool looting. But all these efforts are constantly undermined by the antiquities trade that Cuno finds so benign.

Cuno recommends bringing back partage, a system by which objects excavated in archaeological digs were divided between the country of origin’s cultural authority (usually its national museum) and the archaeologist’s home institution. It was through partage that many American museums assembled distinguished antiquities collections early in the 20th century. The custom dried up in later decades as national museums sought to build up their own collections and, not coincidentally, as American art museums sharpened their appetites for looted antiquities.

Cuno’s call to bring back partage is worthy and constructive (I make a similar suggestion in my own book, Stealing History). But then he reasserts the prerogative of museums to acquire looted antiquities. Give it to them legally or they may have no choice but to take it illegally, seems to be the message here. No one can blame him for wanting museums to have the best material available, but does he realize how much he poisons his own argument in favor of legal mechanisms for acquiring antiquities by defending the illegal ones? Only a few pages before his plea for partage, he makes this hair-raising statement: “If undocumented antiquities are the result of looted (and thus destroyed) archaeological sites, that there is still a market for them anywhere is a problem. Keeping them from U.S. art museums is not a solution, only a diversion.”

As has been amply demonstrated in the last couple of years, U.S. art museums are (or at least were) the market for undocumented antiquities, including the cream of many ancient civilizations. These museums have acted as taste-makers and ethical tone-setters for private collectors, who donate their choicest pieces to museums in exchange for tax deductions. That’s the way this system works, and Cuno knows it.

He notes that “[t]he acquisition of antiquities by U.S. art museums has declined dramatically over the past five years.” After the scandals at the Getty, the Met, and other institutions, museums are reported to have tightened their acquisitions policies. But reading Cuno’s book, one wonders if the underlying thinking about antiquities has changed at all and if museums are not simply hunkering down until the day when they can return to the old practices of pillage, fencing operations, and phony documents.

Later in his book he asserts that modern countries have no claim at all to objects produced in antiquity within their modern borders–no more than anybody else, that is. “Whatever it is, Iraqi national culture certainly doesn’t include the antiquities of the region’s Sumerian, Assyrian, and Babylonian past,” he writes. He expresses similar views about Italy, Turkey, and even the U.S., where, he claims, we are all in agreement that ancient artifacts have nothing to do with our cultural identity. For Cuno, cultural property laws “perpetuate the falsehood that living cultures necessarily derive from ancient cultures.” The memory of ancient cultures has been so erased by migration, war, and cultural change that we have no relation to them anymore except as appreciators of their art objects, ideally in those encyclopedic museums.

This is a provocative, even brave opinion, one that won’t win Cuno any friends in national culture ministries. It is based on an extremely literal understanding of the motives behind laws designed to protect cultural property. Cuno’s argument boils down to the idea that since Italy did not exist when ancient sites were created, its laws relating to those sites are invalid and U.S. courts should ignore them.

But Italy’s government is not just the owner, in the strictest legal sense, of ancient sites, but also the custodian of them for the public good. The state has an interest in preserving the knowledge contained in ancient sites and preventing that knowledge from being lost forever through looting. The only way to exercise that interest is to regulate the way the resource is used, as the state does with a whole range of things, from water, to forests, to migratory birds. Cultural property protection laws are not declarations of nationalistic principle, as Cuno believes. They are policy instruments–blunt ones, to be sure–and they probably push some legitimate or benign transactions underground. So be it. Countries with rich archaeological heritages have decided they have a responsibility to protect them against looters and their enablers like Cuno. They won’t always succeed, they may go overboard, and their arguments may be shot through with ugly nationalism. For all their obvious faults, however, these laws act as one of the few impediments to the looting and illegal export of archaeological artifacts.

Cuno puts himself on firmer ground in his criticism of China’s cultural property practices and its request for a bilateral deal with the United States that would cover art dating up to 1911, an absurd overreach that has little to do with preservation of archaeological sites. By the time I reached his disquisition on China, however, I was doubting Cuno’s intentions and even his judgment. There are certainly good arguments for a legal trade in archaeologically excavated material that American museums could acquire. But Cuno doesn’t have them.

ARCHAEOLOGY contributing editor Roger Atwood is author of Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World.